Antidepressants: An Interactive Evidence Review

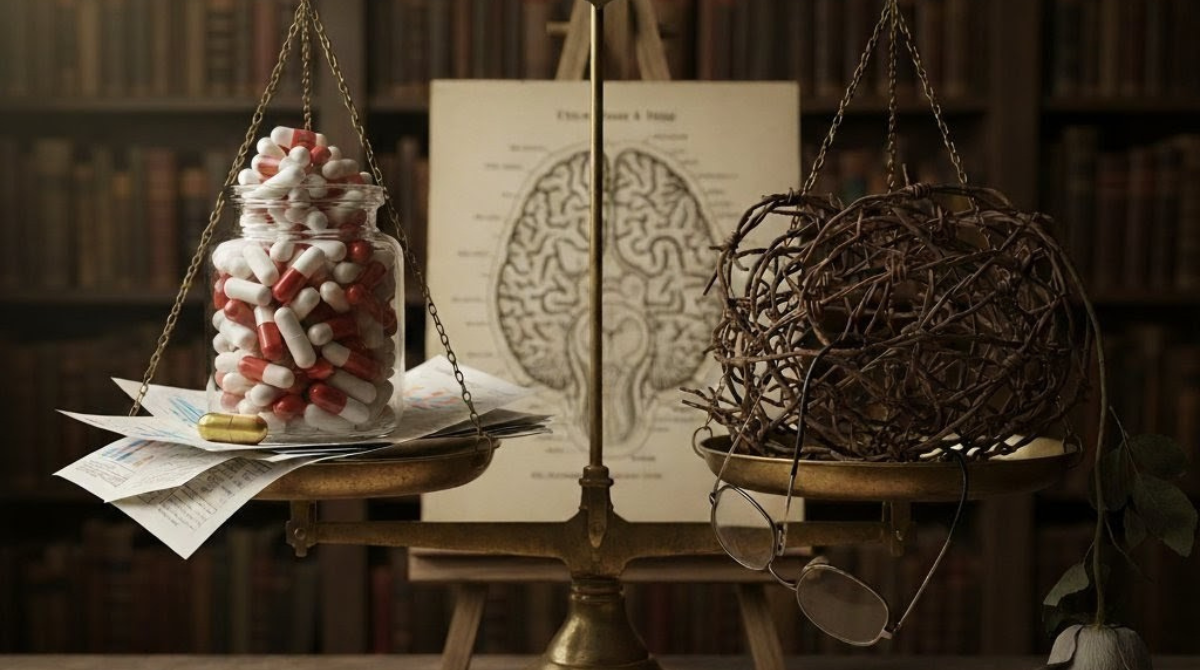

An exploration of the data on efficacy, the power of placebo, and the potential for harm, designed to foster a more informed conversation about mental health treatment.

The Small Drug Effect

Meta-analyses of pharmaceutical trials reveal that the specific biochemical effect of an antidepressant accounts for only a small fraction of patient improvement. The majority of the benefit comes from the powerful placebo effect and other factors common to both groups, such as the hope and expectation that come with entering treatment.

The STAR*D Trial: A Closer Look

The STAR*D trial is often cited to claim a ~67% cumulative remission rate. However, this figure is a theoretical calculation that unrealistically assumes no patients drop out. The reality is that with each successive treatment step, more patients dropped out than achieved remission. **Use the interactive slider below to see the actual, step-by-step outcomes.**

👆 SLIDE TO EXPLORE TRIAL PROGRESS

Acknowledging the Risks

Beyond questions of efficacy, it's crucial to consider the potential for harm. Stopping the medication can induce a withdrawal syndrome distinct from the original condition, and long-term use is associated with a range of serious health risks.

Common Withdrawal Symptoms

Potential Long-Term Harms

Cardiovascular Issues

Studies link long-term use to increased risks of heart disease and stroke.

Emotional Numbing

Many users report feeling blunted, unable to experience a full range of emotions.

Metabolic Changes

Significant weight gain and an increased risk for type 2 diabetes are common.

Sexual Dysfunction

Decreased libido and other sexual problems are among the most persistent side effects.

The Myth of the Chemical Imbalance

The idea that depression is caused by a simple "chemical imbalance" of serotonin was a powerful marketing tool, but it is not supported by scientific evidence. Decades of research have failed to find a consistent link, leading scientists to conclude that depression is a far more complex condition.

The Old Story

Low serotonin levels in the brain cause depression. Taking an SSRI corrects this imbalance.

The Evidence-Based View

There's no proven link. Depression is a complex experience involving genetic, environmental, and psychological factors. Antidepressants alter brain chemistry, but how this relates to mood is not fully understood.

A Critical Methodological and Quantitative Analysis of Antidepressant Efficacy and Adverse Outcome Burdens

Executive Summary: Re-evaluating the Risk-Benefit Calculus

The prevalent clinical and public understanding of antidepressant action—that these medications correct an underlying chemical imbalance—is contradicted by sophisticated methodological analyses of clinical trial data. Decades of research, particularly systematic meta-analyses incorporating previously concealed industry data, demonstrate that the statistical benefit of active antidepressants over placebo is marginal, context-dependent, and largely confined to the most severely depressed cohort. Crucially, this marginal efficacy is systematically offset by the high prevalence and severity of adverse effects, including chronic sexual dysfunction, emotional blunting, and severe discontinuation syndromes. The evidence strongly suggests that much of the reported symptomatic improvement is attributable to powerful contextual effects, particularly the placebo response enhanced by the active drug’s side effects, rather than specific pharmacological action designed to reverse a disease state. Consequently, the established risk-benefit calculus for antidepressants, particularly for long-term users and those with mild-to-moderate depression, appears unfavorable.

I. The Falsification of the Disease-Centered Model and Alternative Mechanism

The justification for the widespread use of antidepressants, specifically Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs), has historically rested upon the disease-centered model of drug action.1 This model posits that psychiatric drugs work by reversing or partially reversing an underlying biological abnormality, such as the widely disseminated belief that depression results from a “chemical imbalance,” specifically low levels of serotonin.2 Rigorous contemporary research has fundamentally challenged this premise.

A. Critique of the Serotonin Hypothesis

The rationale behind SSRIs, introduced in the 1990s, was that they would boost low serotonin levels, thereby correcting the presumed chemical deficiency.3 However, an umbrella review synthesizing data from all major areas of research linking serotonin and depression found no convincing evidence of low serotonin or any consistent serotonin abnormality in individuals diagnosed with depression.3 This research demonstrates a clear lack of evidence supporting the notion that depression is caused by a serotonin deficiency.3

If depression is not caused by low serotonin, the fundamental premise justifying SSRI usage is invalidated.2 This necessitates a critical re-evaluation of how and why these drugs are prescribed. The non-existence of the presumed biological target means that clinical improvement cannot be logically attributed to the “correction” of an underlying disease state.5 The collapse of the theoretical justification shifts the focus of inquiry from whether the drug fixes a disease to whether the drug’s psychoactive effects are useful, a subtle but profound theoretical distinction that carries significant ethical and clinical implications.5

B. The Drug-Centered Model: Mechanism of Altered States

In place of the discredited disease-centered approach, the drug-centered model provides an alternative understanding of pharmacological action.1 This model emphasizes that psychiatric drugs modify normal brain processes, inducing an altered mental state that subsequently impacts emotional and behavioral problems (i.e., symptoms).5 In this framework, the drug is not a targeted treatment for a known deficit but a general mind and behavior modifier.1

A key observation supporting this model is the effect known as emotional blunting. SSRIs blunt both negative and positive emotions.3 While this may provide temporary relief for individuals experiencing acute distress or unhappiness by reducing the intensity of suffering, it is understood as a drug-induced alteration of normal affect, not a restorative mechanism.6

Furthermore, the delay often observed in symptomatic improvement—weeks following the commencement of treatment—is not explained by the chemical correction of a simple imbalance, which should occur rapidly. Instead, the evidence suggests that antidepressant administration, even a single dose, can induce a cognitive shift, biasing perception toward positive information.7 The subsequent symptomatic relief is thought to require the time necessary for this new, more positive bias to be “enacted” through ongoing interactions with the social environment, leading to the development of new positive associations.8 Therefore, the symptomatic relief observed is the result of a secondary psychological process facilitated by the drug’s primary psychoactive effect (emotional and cognitive alteration), which is distinct from reversing an abnormality.7

II. Quantifying Marginal Efficacy: The Role of Reporting Bias

The assertion that antidepressants are largely ineffective stems from meticulous scrutiny of placebo-controlled clinical trial data, which reveals that the true pharmacological benefit is often negligible, especially once methodological biases are accounted for.

A. Minimal Difference in Standardized Mean Differences (SMD)

The efficacy of modern antidepressant treatments is quantitatively modest. Standardized mean differences (SMDs) over placebo in current clinical trials are typically around 0.30.9 While mathematically similar to treatments for other chronic illnesses, this effect size is regarded as “less than impressive” in the context of psychiatric pharmacology.9

Historically, robust drug-placebo differences were observed in early trials involving severely ill and hospitalized patients. However, these substantial differences have not been sustained in trials conducted over the past two decades.9 This narrowing of the drug-placebo gap is partially attributed to the broadening of the definition of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), which includes more patients with mild to moderate illness, a population where the drug-placebo difference is minimal.9

B. The Impact of Publication and Reporting Bias (FDA Re-analysis)

A major distortion in the public perception of antidepressant efficacy resulted from systemic publication bias within pharmaceutical research. Influential critics, such as Irving Kirsch, conducted meta-analyses that incorporated previously unpublished clinical trial data submitted to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for regulatory approval.10 The inclusion of these non-published, often negative, trials drastically reduced the apparent efficacy.

Analyses comparing published data with the complete data set (published plus unpublished FDA reports) demonstrated severe inflation of reported efficacy. For various antidepressants, the effect sizes calculated from the published efficacy data were found to be inflated by 11% to 69% compared to effect sizes calculated using the full FDA data.12 Overall, the published literature inflated the apparent effect size for older antidepressants by 32%.13 This systematic inflation occurs because trials with negative findings experience a significantly longer median time to publication (4.2 years) compared to trials with positive findings (2.2 years).14 This methodological bias systematically favors the dissemination of positive outcomes, resulting in a clinically misleading evidence base.12 When all available trial data are considered, the purported benefit of antidepressants often fails to meet established criteria for clinical significance.10

C. Severity-Dependent Efficacy (The Kirsch Findings)

Meta-analyses that stratify efficacy by baseline severity consistently yield a critical finding: the measurable difference between the active drug and placebo is only statistically and clinically significant in patients suffering from severe depression.10 For patients with mild or moderate depression, the drug benefit is statistically negligible.16

However, the mechanism behind this severity-dependent efficacy is not an enhanced pharmacological action of the drug. Research by Kirsch and colleagues found that the larger drug-placebo difference observed in severe depression results from a poorer response to placebo among the most profoundly ill patients.20 The true, specific pharmacological effect of the drug appears to be constant, regardless of the patient’s depression severity.21 The powerful contextual effect of the placebo, which is robust in mild cases, diminishes significantly when patients are extremely depressed and perhaps incapable of sustaining positive expectation or hope.20 Thus, the drug appears superior in severe cases only because the contextual healing mechanisms fail, leaving the small, constant drug effect visible.

Table 1: Antidepressant Efficacy vs. Placebo Effect Magnitude (Kirsch/FDA Data Re-analysis)

| Source (Meta-analysis) | Focus Population | Effect Size Magnitude | Impact of Bias/Severity | Key Implication for Efficacy |

| Kirsch et al. (1998/2008) | New Generation Antidepressants (Full Data) | Modest (often SMD) | Only of improvement variance attributed to active drug.23 | Benefit falls below accepted criteria for clinical significance.10 |

| FDA Data Re-analysis (Turner, et al.) | Antidepressants (Published vs. Full Data) | Published efficacy reduced by 12 | Systematic inflation of positive results in published literature. | Published literature presents a misleadingly optimistic efficacy profile.12 |

| Severity Stratification (2008) | Mild/Moderate Depression | Not Clinically Significant | Difference due to poorer placebo response in severe patients.20 | Drug efficacy is marginal unless placebo effects are suppressed by illness severity.16 |

The quantitative implication of these findings is that the value of Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) as the standard tool for assessing antidepressant efficacy is fundamentally doubtful.21 If publication bias inflates reported effects by up to 69% 12 and the standard inert placebo fails to isolate the drug’s true action, the clinical utility derived from published trials is questionable.

III. The Placebo Effect: The Engine of Apparent Improvement

The overwhelming contribution of the placebo effect is the most substantial evidence supporting the claim that mood changes are predominantly driven by expectation and contextual factors, not specific drug mechanisms.

A. Magnitude and Consistency of the Placebo Response

In double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, the response rates observed in the placebo group are consistently high, averaging between 35% and 40%.24 This substantial response rate forms the baseline against which all pharmacological improvements are measured.24 Research suggests that, contrary to some clinical assumptions, the average placebo response rate has remained stable for more than 25 years.24 Therefore, the diminishing drug-placebo difference observed in recent decades is not due to a rising placebo effect, but rather a failure of the drug to demonstrate significantly greater efficacy.25

B. The Unblinding Phenomenon and Enhanced Expectation

The methodological gold standard of blinding, intended to separate the specific drug effect from the contextual placebo effect, frequently fails in antidepressant trials. Active antidepressants commonly produce noticeable side effects (such as dry mouth, insomnia, or nausea) that are absent in the inert placebo.11

The occurrence of these side effects often leads to the unblinding of both the patient and the investigator, allowing them to correctly guess the treatment group assignment at levels exceeding chance.22 This certainty of receiving the “active drug” triggers a positive expectancy, significantly enhancing the placebo effect specifically for the drug group.23 The observed small benefit of the drug is thus frequently a super-placebo effect, an expectation-related response amplified by the psychoactive effects of the drug that break the blind.11 This unblinding effect can also lead to biased outcome ratings by clinicians, further inflating perceived drug efficacy.26

The critical realization is that expectation is not merely additive to the drug’s effect; rather, the drug’s side effects facilitate and maximize the expectation effect.21

C. The Active Placebo Gold Standard

A methodology designed to mitigate the unblinding effect is the use of active placebos, which mimic the common, non-mood-altering side effects of the antidepressant.27 If the active drug truly possesses a specific efficacy beyond the contextual effects, the drug should still show a strong superiority over the active placebo.

However, meta-analyses that have compared antidepressants against active placebos demonstrate that the differences in efficacy are notably small.27 In one analysis, the pooled estimate of effect favoring the antidepressant was found to be highly sensitive to the inclusion of strongly positive trials; omitting a single such trial reduced the pooled effect size significantly, suggesting that unblinding effects are a pervasive contaminant that inflates efficacy estimates in trials using inert placebos.27

Given that the small, specific drug effect relies heavily on methodological contamination (unblinding) for its statistical significance, the clinical response observed in most patients is better explained by non-pharmacological, contextual healing mechanisms. Indeed, alternative treatments such as psychotherapy and physical exercise produce benefits comparable to antidepressants, critically, without the pharmacological side effects and inherent health risks.11 Furthermore, psychotherapy and placebo treatments exhibit lower relapse rates than antidepressant medication.11

IV. Assessing the Cumulative Burden of Harm: Long-Term Consequences

The discussion of antidepressant efficacy must be balanced against the cumulative burden of harm, which is often severely underestimated due to methodological flaws in clinical trial design.

A. Prevalence of Common and Acute Adverse Effects

A systematic review of patients’ long-term experiences with antidepressants reveals a staggeringly high frequency of adverse effects.29 The prevalence of these harms far exceeds the marginal benefit demonstrated in most efficacy studies:

- Withdrawal effects (73.5%).29

- Sexual difficulties (71.8%).29

- Weight gain (65.3%).29

- Feeling emotionally numb (64.5%).29

- Failure to reach orgasm (64.5%).29

Crucially, these are not merely mild inconveniences; between 36% and 57% of participants reported experiencing these effects at a moderate or severe level.29 This high rate of severe, life-altering adverse effects underscores the significant risk undertaken for a potentially marginal therapeutic gain.

B. The Unrecognized Dangers of Dependence and Withdrawal

The discontinuation of antidepressants, especially after prolonged use, frequently leads to Antidepressant Discontinuation Syndrome (ADS), also referred to as withdrawal.30 Symptoms can be debilitating and include severe anxiety, insomnia, vivid dreams, headaches, dizziness, flu-like symptoms, and electric shock sensations (often termed “brain zaps”).30

While conventionally classified as discontinuation syndrome rather than addiction, the severity and prevalence of these symptoms, coupled with the difficulties many patients experience in stopping the medication, constitute a state of physiological dependence that was largely unanticipated during the rollout of newer drug classes.32 Certain drug classes, including venlafaxine and paroxetine, are associated with a particularly increased risk of severe or prolonged withdrawal manifestations.31 The failure to adequately appreciate the risks involved in taking drugs that alter brain function long-term means patients frequently lack the necessary information to make informed decisions regarding cessation.3

C. Persistent and Enduring Harms

Some adverse effects persist long after the medication has been stopped, representing enduring damage. Post-SSRI Sexual Dysfunction (PSSD) involves sexual impairment (loss of libido, genital hypersensitivity, failure to reach orgasm) that can continue for months, and sometimes years, following cessation.32 The consistency of this syndrome with acute SSRI effects and corroboration from animal research supports PSSD as a genuine, long-term consequence of drug use rather than a resurgence of underlying depression.32

Furthermore, the intentional effect of emotional blunting, which may provide acute relief, becomes a chronic harm for many. Patients report feeling emotionally numb, “not like myself,” and experiencing reduced positive feelings.29 This trading of acute distress for general emotional flatness represents a significant compromise to well-being that must be properly weighed against marginal clinical benefit.6

D. The Critical Trial Duration Discordance

The true long-term risks are systematically obscured by a fundamental misalignment between the duration of regulatory clinical trials and real-world prescribing practices.34

| Usage Metric | Clinical Trial Data | Real-World Usage (U.S.) |

| Median Duration | 8 weeks (IQR: 6-12 weeks) 34 | 5 years (260 weeks) 34 |

The median duration of regulatory trials is 8 weeks, with only a small fraction of trials extending beyond 12 weeks, and none exceeding 52 weeks.34 Conversely, the median duration of antidepressant use in the United States is approximately five years.34 This methodological discrepancy means that the data used for drug approval cannot possibly capture the severe, chronic, and dependence-related adverse events associated with prolonged use. The failure is compounded by the fact that only 3.8% of reviewed trials monitored for withdrawal symptoms.34 This systemic regulatory blind spot ensures that the comprehensive risk profile of long-term use remains largely unknown at the point of prescription, hindering the ability of patients to provide genuinely informed consent.33

Table 2: Long-Term Harms and Prevalence of Adverse Effects (Patient-Reported Data)

| Adverse Event Category | Prevalence Among Long-Term Users | Clinical Detail/Nature of Harm | Persistence |

| Withdrawal Effects (ADS) | 29 | Anxiety, electric shock sensations, flu-like symptoms, rebound phenomena 30 | Typically weeks, but can be prolonged 31 |

| Sexual Dysfunction | 29 | Loss of libido, failure to reach orgasm 29 | Can persist for months/years after cessation (PSSD) 32 |

| Emotional Numbness | 29 | Reduced positive feelings, feeling “not like myself,” caring less about others 29 | Persistent during treatment 6 |

| Weight Gain | 29 | Potential long-term metabolic risks 29 | Persistent during treatment 29 |

V. The Risk-Benefit Equation: NNT vs. NNH Analysis

To accurately evaluate the claim that antidepressants cause more harm than good, it is necessary to employ quantitative epidemiological metrics that juxtapose therapeutic benefit against the risk of adverse outcomes.

A. Defining NNT and NNH

The Number Needed to Treat (NNT) is the statistic representing how many patients must receive the treatment for one additional patient to experience a favorable outcome (e.g., response) compared to placebo.35 A single-digit NNT (typically ) is generally considered favorable.36

The Number Needed to Harm (NNH) represents the number of patients who must receive the treatment for one additional patient to experience a specified adverse outcome compared to placebo.35 For a treatment to be definitively favorable, the NNH must be substantially greater than the NNT.36

B. Juxtaposing Benefit and Harm Statistics

Clinical trial data reveal a tenuous balance between benefit and harm. For example, in short-term trials of the antidepressant levomilnacipran for MDD, the NNT for response was 9, meaning nine patients were treated to achieve one additional positive responder compared to placebo.35

In the same set of trials, the NNH for dropout due to adverse events (AEs) was 19.35 The NNH for various specific adverse effects ranged from 10 to 31.35 This means that for every nine patients treated to gain one marginal responder, 19 patients must be treated to cause one patient to drop out due to severe side effects.35

This narrow margin between NNT (9) and NNH (19) compromises the favorable profile, forcing clinicians into a difficult subjective trade-off.35 The comparison must also consider that the reported NNT is only for the marginal benefit over the already high placebo response rate (35–40% response rate on placebo).24 Consequently, while the NNT for additional response may be low, the NNH for highly prevalent, debilitating adverse effects, such as sexual dysfunction (experienced by over 70% of long-term users) 29, is often very close to the NNT for marginal benefit.

The clinical profile is further undermined by the finding that out of 21 studied antidepressants, only two had fewer overall dropouts compared with placebo, underscoring the general poor tolerability across the class.38

C. The Value Judgment Dilemma

The tight NNT/NNH ratio highlights that the drug effect is marginal enough that the decision to prescribe becomes a profound value judgment regarding risk acceptance. For instance, in the case of levomilnacipran, the Likelihood to be Helped or Harmed (LHH) ratio (NNH/NNT) is . This low ratio indicates that the likelihood of receiving an extra benefit versus experiencing an adverse event severe enough to cause discontinuation is precariously balanced, especially when considering the severity of certain harms, such as suicidal ideation (reported by 36% of participants in one systematic review).29

For patients with mild or moderate depression, where the NNT for benefit is effectively infinite due to the lack of clinical significance over placebo 16, the decision to prescribe subjects them to the high risks of dependence and chronic harm with no scientifically validated unique benefit. Given the widespread issue of chronic and persistent harms like PSSD 32, which were not adequately captured by the short-term NNH statistics, the evidence suggests that the balance is unfavorable for a substantial cohort of long-term users.

Table 3: Risk-Benefit Comparison (NNT vs. NNH for Specific Outcomes)

| Antidepressant/Trial Cohort | Outcome | NNT (Additional Benefit) | NNH (Additional Harm) | Implied LHH (Likelihood to be Helped/Harmed) |

| Levomilnacipran (8-10 weeks) | Response | 9 35 | 19 (Dropout due to AEs) 35 | 2.1 (Low margin of benefit over high-threshold harm) |

| SPRAVATO (Pooled short-term) | Acute Remission | 7 40 | 33 (Discontinuation due to AEs) 40 | 4.7 |

| General SSRI Trials | Response (Pooled Estimates) | 5 to 10 36 | NNH for common AEs (e.g., 10-31) 35 | NNH often approaches NNT, compromising favorable profile 36 |

Conclusion and Implications: Moving Beyond the Pharmacological Fix

The extensive research challenging the efficacy and safety profile of modern antidepressants yields several definitive conclusions.

First, the foundational scientific theory of antidepressant action—the chemical imbalance hypothesis—has been discredited by comprehensive systematic reviews.2 This mandates a shift away from the disease-centered model, recognizing that symptomatic relief, when it occurs, is achieved through the drug-induced alteration of normal mental states (such as emotional blunting) rather than the correction of a biological deficit.5

Second, the actual statistical efficacy of these drugs is profoundly marginal. Meta-analyses that correct for systemic publication bias—which inflated published results by up to 69% 12—demonstrate that the benefit over placebo falls below clinically significant criteria for most patients.10 The measurable difference observed in severe depression is primarily an artifact of the placebo effect failing in the most severely ill, not a heightened specific drug action.20

Third, the primary driver of apparent improvement is the placebo response, which is amplified in the drug group because the side effects inadvertently unblind participants and raise expectations.19 Trials using active placebos demonstrate that when blinding is maintained, the drug-placebo difference largely disappears.27 The evidence strongly supports the case that the mood changes observed are highly likely to be the result of context and expectation, not specific drug actions.

Finally, the marginal benefit is quantitatively outweighed by a high burden of harm. The majority of long-term users experience severe sexual difficulties, emotional blunting, and dependence symptoms.29 This risk profile is systematically underreported because regulatory trials (median duration of 8 weeks) fail to assess the harms associated with real-world chronic use (median duration of 5 years).34 When NNTs are juxtaposed against NNHs, the resulting ratios indicate that the decision to treat is one of precarious balance, particularly for the large population with mild-to-moderate depression who derive no unique pharmacological benefit.

The data collectively suggest that the rising global use and long-term prescribing of antidepressants subjects millions of individuals to unnecessary chronic side effects 39 for a benefit that can often be replicated by non-pharmacological methods like psychotherapy and exercise, which offer comparable efficacy and lower relapse rates without the pharmacological risks.11 This evidence calls for a radical reform of clinical guidelines and a transparent communication of these risks to ensure genuine informed consent.

Works cited

- Models of drug action | Joanna Moncrieff, accessed October 7, 2025, https://joannamoncrieff.com/2013/11/21/models-of-drug-action/

- Finding a Balance in the Chemical Imbalance Theory | Psychiatric News – Psychiatry Online, accessed October 7, 2025, https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2023.02.12.28

- How to take the news that depression has not been shown to be caused by a chemical imbalance | Joanna Moncrieff, accessed October 7, 2025, https://joannamoncrieff.com/2022/07/24/how-to-take-the-news-that-depression-has-not-been-shown-to-be-caused-by-a-chemical-imbalance/

- Is the serotonin hypothesis/theory of depression still relevant? Methodological reflections motivated by a recently published umbrella review – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed October 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9957868/

- Research on a ‘drug-centred’ approach to psychiatric drug treatment: assessing the impact of mental and behavioural alterations produced by psychiatric drugs, accessed October 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6998955/

- Against the stream: Antidepressants are not antidepressants – an alternative approach to drug action and implications for the use of antidepressants | BJPsych Bulletin – Cambridge University Press, accessed October 7, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/bjpsych-bulletin/article/against-the-stream-antidepressants-are-not-antidepressants-an-alternative-approach-to-drug-action-and-implications-for-the-use-of-antidepressants/576198D6AEA703B318251B38B2FAE43E

- Toward a Neuropsychological Theory of Antidepressant Drug Action: Increase in Positive Emotional Bias After Potentiation of Norepinephrine Activity – Psychiatry Online, accessed October 7, 2025, https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.ajp.160.5.990

- Cognitive neuropsychological theory of antidepressant action: a modern-day approach to depression and its treatment – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed October 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8062380/

- Antidepressants versus placebo in major depression: an overview – PMC, accessed October 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4592645/

- Initial Severity and Antidepressant Benefits: A Meta-Analysis of Data Submitted to the Food and Drug Administration | PLOS Medicine – Research journals, accessed October 7, 2025, https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.0050045

- Placebo Effect in the Treatment of Depression and Anxiety – PMC, accessed October 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6584108/

- Effect of reporting bias on meta-analyses of drug trials – The BMJ, accessed October 7, 2025, https://www.bmj.com/content/344/bmj.d7202

- Publication Bias in Antipsychotic Trials: An Analysis of Efficacy Comparing the Published Literature to the US Food and Drug Administration Database | PLOS Medicine, accessed October 7, 2025, https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1001189

- Time-Lag Bias in Trials of Pediatric Antidepressants: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis – National Institutes of Health (NIH) |, accessed October 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3645909/

- The cumulative effect of reporting and citation biases on the apparent efficacy of treatments: the case of depression – PMC, accessed October 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6190062/

- Meta-analysis shows difference between antidepressants and placebo is only significant in severe depression | The BMJ, accessed October 7, 2025, https://www.bmj.com/content/336/7642/466.1

- Meta-analysis shows difference between antidepressants and placebo is only significant in severe depression – PMC, accessed October 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2258366/

- Critiquing the Critique: Resisting Commonplace Criticisms of Antidepressants in Online Platforms – PMC, accessed October 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8649826/

- Placebo Effect in the Treatment of Depression and Anxiety – Frontiers, accessed October 7, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychiatry/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00407/full

- Initial Severity and Antidepressant Benefits: A Meta-Analysis of Data Submitted to the Food and Drug Administration, accessed October 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2253608/

- Efficacy of antidepressants: a re-analysis and re-interpretation of the Kirsch data – Oxford Academic, accessed October 7, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/ijnp/article/14/3/405/906146

- Antidepressants and the Placebo Effect – PMC, accessed October 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4172306/

- Antidepressants and the placebo response | Request PDF – ResearchGate, accessed October 7, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/41506832_Antidepressants_and_the_placebo_response

- Placebo response rates in antidepressant trials: A systematic review of published and unpublished double-blind randomised controlled studies | Request PDF – ResearchGate, accessed October 7, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309031495_Placebo_response_rates_in_antidepressant_trials_A_systematic_review_of_published_and_unpublished_double-blind_randomised_controlled_studies

- A Model of Placebo Response in Antidepressant Clinical Trials – Psychiatry Online, accessed October 7, 2025, https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12040474

- Lessons learned from placebo groups in antidepressant trials – PMC, accessed October 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3130402/

- Active placebos versus antidepressants for depression – PubMed, accessed October 7, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14974002/

- Active placebos versus antidepressants for depression – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed October 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8407353/

- Long-term antidepressant use: patient perspectives of benefits and adverse effects – PMC, accessed October 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4970636/

- Antidepressant withdrawal: Is there such a thing? – Mayo Clinic, accessed October 7, 2025, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/depression/expert-answers/antidepressant-withdrawal/faq-20058133

- Antidepressant Withdrawal and Rebound Phenomena – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed October 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6637660/

- Persistent adverse effects of antidepressants – PMC, accessed October 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8061256/

- Opinion: New antidepressant withdrawal review may downplay symptoms | UCL News, accessed October 7, 2025, https://www.ucl.ac.uk/news/2025/jul/opinion-new-antidepressant-withdrawal-review-may-downplay-symptoms

- Antidepressant Trial Duration versus Duration of Real-World Use: A Systematic Analysis, accessed October 7, 2025, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.02.27.25323057v1.full-text

- The Numbers Needed to Treat and Harm (NNT, NNH) Statistics: What They Tell Us and What They Do Not – Psychiatrist.com, accessed October 7, 2025, https://www.psychiatrist.com/jcp/numbers-needed-treat-harm-nnt-nnh-statistics-tell/

- NNT & NNH — ADHD Practical Guide / Tris Pharma Medical Affairs, accessed October 7, 2025, https://www.trisadhdbooksforhcps.com/clinician/NNT-NNH

- Practising evidence-based medicine in an era of high placebo response: number needed to treat reconsidered – PMC, accessed October 7, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4853640/

- Considering the methodological limitations in the evidence base of antidepressants for depression: a reanalysis of a network meta-analysis | BMJ Open, accessed October 7, 2025, https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/9/6/e024886

- Challenging the new hype about antidepressants – Joanna Moncrieff, accessed October 7, 2025, https://joannamoncrieff.com/2018/02/24/challenging-the-new-hype-about-antidepressants/

- SPRAVATO – Number Needed to Treat or Harm – Post Hoc Analysis – J&J Medical Connect, accessed October 7, 2025, https://www.jnjmedicalconnect.com/products/spravato/medical-content/spravato-number-needed-to-treat-or-harm-post-hoc-analysis